Main Second Level Navigation

Dec 13, 2023

Unraveling the enigma of Nodding Syndrome

Programs: Graduate, Agile education, Research: Brain & Neuroscience, Inclusive community

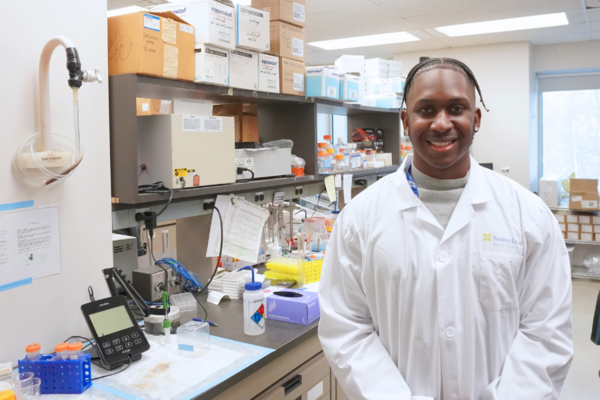

Kenneth Kodja

The team in Uganda (from left to right): Dr. Sylvester Onzivua, Dr. Michael Pollanen, Joe Otto, MSc student Kenneth Kodja, George Otto